Charts of Matthew Flinders

Celebrating the cartographer who circumnavigated Australia.

Matthew Flinders’ final journey, centuries after he put Australia on the map

The British Naval Captain Matthew Flinders (1774 - 1814) could never have imagined that he would be reburied with fanfare in 2024, almost 200 years after his extraordinary life was cut short.

But that’s exactly what is planned from July 12, 2024, when he will be laid to rest in his birthplace in England, after his missing coffin was finally found.

However, no amount of fanfare could fully account for the life of the bold and brave explorer, who became one of the world's greatest maritime adventurers, and whose circumnavigation and mapping of Australia was the pinnacle of his career.

Ultimately, though, it all came at a huge personal cost that saw Flinders lose everything he loved and sent him to an early grave.

Hand coloured engraving of Captain Matthew Flinders RN.

Joyce Gold, published by the Naval Chronicle Office.

Flinders - first, fascinating and fearless

Flinders made maritime history when he was in his twenties. The British Naval officer was a man of determination who left a legacy of historic and extraordinary achievements still revered today, adventures most couldn’t imagine – all peppered with romance and tragedy.

Flinders was also a fascinating personality, a fearless explorer and naval captain who hated warfare and was a romantic at heart, writing tender love letters to his wife

– Author and Flinders expert, Grantlee Kieza.

But by the time he was twenty-nine, Flinders had been jailed, and his career was over. He was also denied the glory of his remarkable achievement, his freedom and his adored wife. His death at 40 was painful.

Flinders was buried in London in 1814, but the exact location became a mystery until it was rediscovered in 2019.

Flinders' legacy is so rich, that the unearthing of his coffin immediately set in motion plans for his reburial in July 2024 - a grand naval ceremony in his birthplace of Donington, England.

Matthew Flinders – full of drive and ambition

Matthew Flinders joined the British Royal Navy when he was 15. It was a natural fit for him.

From childhood Flinders was fascinated by the natural world around him. As a boy he was intrigued by the maritime adventure novel Robinson Crusoe which he likened to a match on the straw of his mind.

Flinders was also extremely ambitious to make a name for himself in history and to create some sort of fortune for his family.

– Grantlee Kieza.

Flinders had been expected to follow in the footsteps of his father and grandfather, who were surgeons. He chose his passion instead.

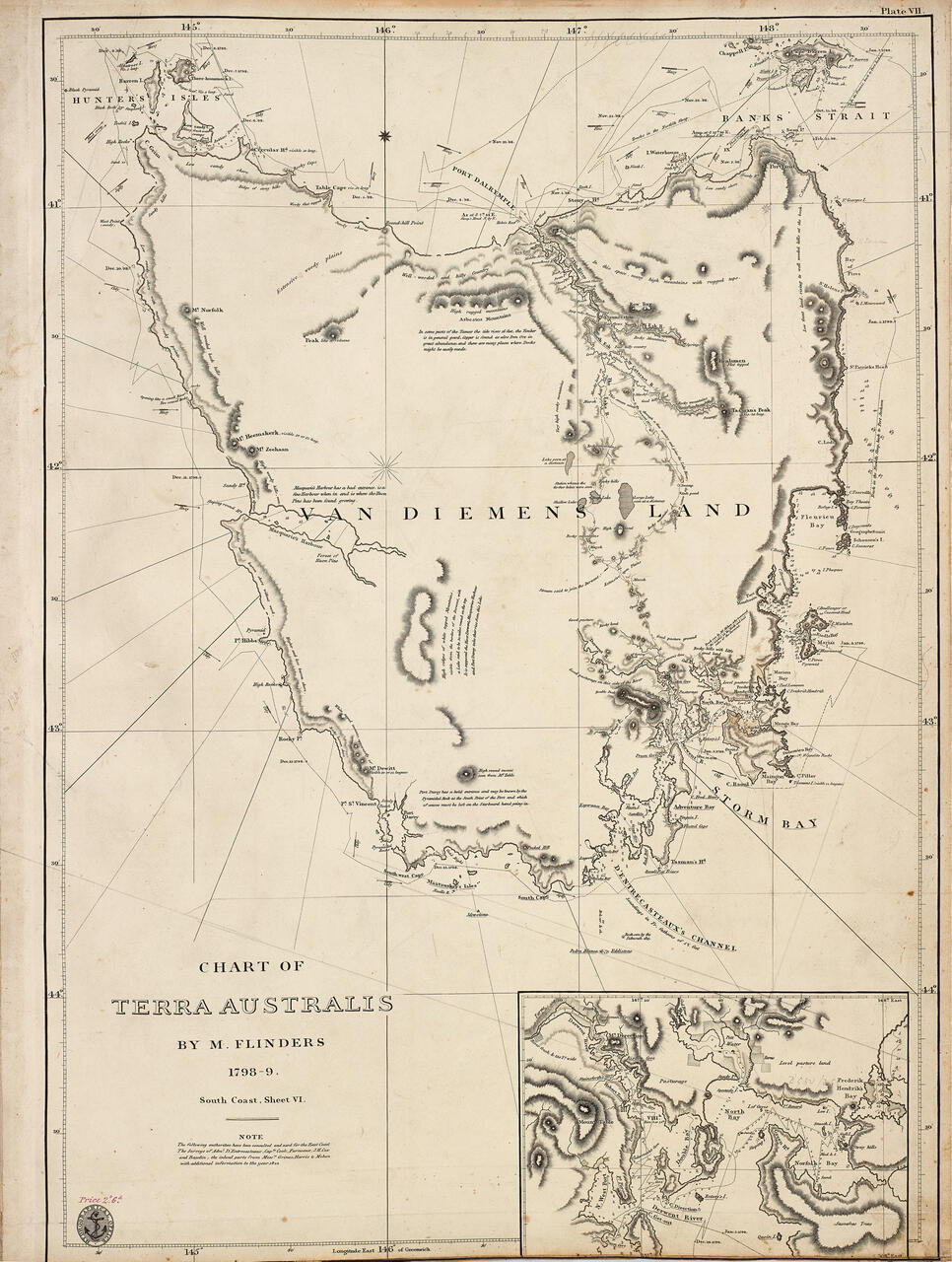

On his journey to becoming a history-making navigator, Flinders sailed with the master seaman, William Bligh, from whom he learnt practical navigation and chart making. Then, while sailing from England to the colony of New South Wales, he befriended ship surgeon, George Bass. They both believed that a strait separated the mainland from Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania) and went there in October 1798 to prove it. Flinders concentrated on charting the island while Bass explored it. Flinders named it Bass Strait.

Flinders then circumnavigated and named Australia

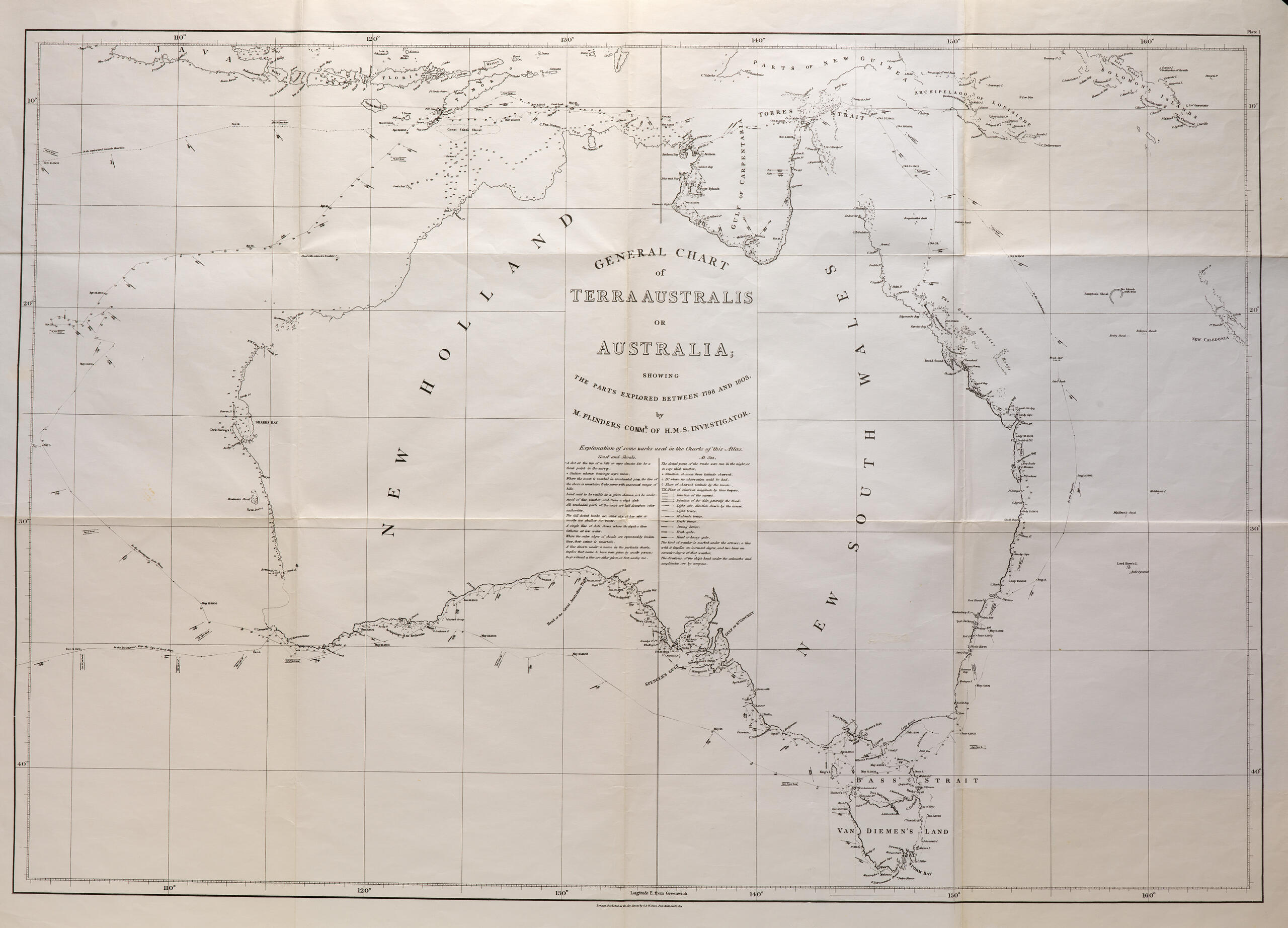

Flinders eventually became commander of the ship, HMS Investigator. He was instructed to go to 'New Holland for the purpose of making a complete examination and survey' of the southern and northern coasts and, if he had time, the rest of the west and the north-west.

At the time, it was thought the lands known as New Holland to the west and New South Wales to the east were separate land masses. Captain Flinders proved otherwise – that they were both part of a single continent. He took three years to circumnavigate it, finishing in 1803.

Flinders also named the land mass.

Model of HMS INVESTIGATOR based on the Matthew Flinders' notes.

© Lynne and Laurie Hadley. ANMM Collection

Flinders repeatedly used the word ‘Australians’ for the indigenous people living here. He also pushed the British government to use the name ‘Australia’ instead of New Holland, which it had been using for what he now proved was an island continent. The first maps he drew after the circumnavigation bore the name ‘Australia’, and the name was eventually adopted.

– Grantlee Kieza.

Flinders had achieved all this by the time he was 29.

Flinders' job was done, and he desperately wanted to get back to his wife

Flinders was in a hurry to return to England to see Ann. At that stage, they hadn’t seen each other in three years – they'd married just three months before Flinders left England on his mission to Australia in 1801.

Flinders wanted Ann to go with him, but the Royal Navy wouldn’t allow it. They were separated for most of their married life and it took almost ten years and many love letters before Flinders and Ann could be reunited.

Contemporary sculpture series titled 'The Lost Letters of Ann Chapelle Flinders', celebrating Flinders relationship with his wife.

© Elizabeth Gertsakis. ANMM Collection

Charts of Matthew Flinders

Flinders’ urgency to return to England resulted in disaster

When Flinders tried to return home, he left behind the damaged Investigator, but there was trouble with his replacement ship, and he was forced to stop for repairs at the French colony, Mauritius.

He also had no idea then that France and England were at war. Flinders was arrested on arrival in Mauritius, accused of being a spy and spent six-and-a-half years under house arrest. Mr Kieza says things could have worked out very differently if Flinders wasn’t so “arrogant and impetuous”.

His ‘bull at a gate’ personality led him to rush home in a dilapidated vessel to see his wife in England after the circumnavigation of Australia.

If he had been more prudent, he would have waited for a more seaworthy vessel and could have avoided having to stop at Mauritius for repairs to his ship.

His greatest achievement – putting Australia on the map - was completed before he was 30.

A ‘broken man’ - Flinders lost his freedom, years of his marriage and then, his beloved cat, Trim

Matthew Flinders had circumnavigated Australia with his cat, Trim, by his side. The black and white feline was with Flinders when he was detained, and the cat was allowed to wander the island. Then one day, in 1804, Trim disappeared.

Mr Kieza says Flinders was devastated.

Trim’s death caused him [Flinders] a great deal of anxiety and the seven years he spent longing for a return to England left him very much a broken man.

Flinders' love of Trim propelled him to write a book about their relationship, which includes this excerpt:

To the memory of

Trim.

the best and most illustrious of his Race, the most affectionate of friends,

faithful of servants and best of creatures.

He made the Tour of the Globe, and a voyage to Australia, which he circumnavigated and was ever the delight and pleasure of his fellow voyagers.

– A Biographical Tribute to the Memory of Trim, Matthew Flinders (c. 1803-1810)

Flinders was finally able to return to England in 1810, and he immediately started preparing charts and documentation of his circumnavigation of Australia. Two years later, he and Ann had a daughter - their only child.

The bad luck continued even after Flinders was buried

Troubled by kidney disease for 20 years, it finally claimed his life after months of pain, and he died in 1814 when he was just 40. Flinders' career choice is believed to be largely responsible for his sickness.

Flinders’ death from kidney disease was no doubt a result of the privations and dehydration he suffered during long ocean voyages

– Grantlee Kieza.

And Flinders died the day after the landmark summary of his life’s work, A Voyage to Terra Australis was published.

Flinders was laid to rest in London, England, but his grave’s location became a mystery. The headstone on Flinders’ grave disappeared in the 1840s, and his remains were lost.

It took almost two centuries to find his grave, which was unearthed during excavation of the burial ground in London January 2019. The discovery sparked a passionate campaign by his descendants and locals, to have Flinders reburied in the town he was born – Donington, England.

Matthew Flinders. ANMM Collection

The legendary seafarer’s final voyage

The campaign succeeded and the ceremony celebrating the life and accomplishments of Matthew Flinders was arranged to span three days, from the 12th of July 2024. Hundreds of guests were invited from across the world, including Australia and Mauritius. The ceremony featuring an 18-gun salute and the burial of Flinders in sacred ground.

A fitting tribute for a determined and passionate man whose accomplishments cost him his career, his loves, his passions and ultimately his life.

Visit the Matthew Flinders Bring Him Home YouTube channel, where the livestream of his reburial will be broadcast on Saturday 13th July 2024.

00001899 - Chart from A voyage to Terra Australia, volume 2. Matthew Flinders, published by G and W Nicol, 1814.

ANMM Collection

Commemorating Matthew Flinders' 250th birthday

On the 16 March 2024, to mark the 250th birthday of Matthew Flinders, the Australian National Maritime Museum published an exclusive extract from Peter FitzSimons’ forthcoming book on the great navigator.

Below, FitzSimons’ writes about Flinders and his attitude to Indigenous Australians.

Commemorative plate featuring Matthew Flinders (1974).

Josiah Wedgwood & Sons Ltd. ANMM Collection

7 April, 1802, Kangaroo Head, the first Australians

On his own voyage up the East Coast of New Holland, as he called it, Captain Cook found the elusiveness of the “Indians” very puzzling. Rarely more than flitting figures in the distance, they seemed to have no interest in any interactions at all, no matter how much they try to entice them.

But perhaps, Captain Flinders wonders, his mighty forebear was trying too hard?

For as they proceed, the protégé of Cook’s protégé, his humble self, develops an entirely different tactic to engage them. Take this day, when calls are heard, native voices, from bodies unseen, yelling to them from dense scrubland:

“No attempt was made to follow them, for I had always found the natives of this country to avoid those who seemed anxious for communication; whereas, when left entirely alone, they would usually come down after having watched us for a few days.”[1]

Eminently sensible, this observation leads Flinders to further musing and empathy on the Indigenous caution that seems beyond his time. After all, Flinders reasons, from that perspective, the response of the natives is exactly what we white people would do.

“For what, in such case, would be the conduct of any people, ourselves for instance, were we living in a state of nature, frequently at war with our neighbours, and ignorant of the existence of any other nation? On the arrival of strangers so different in complexion and appearance to ourselves, having power to transplant themselves over, and even living upon, an element which to us was impossible, the first sensation would probably be terror, and the first movement flight.

“We should watch these extraordinary people from our retreats in the woods and rocks, and if we found ourselves sought and pursued by them, should conclude their designs to be inimical; but if, on the contrary, we saw them quietly employed in occupations which had no reference to us, curiosity would get the better of fear, and after observing them more closely, we should ourselves risk a communication. Such seemed to have been the conduct of these Australians.”[2]

“Australians?” It is the first time that the native population has been so called, and it has a certain ring to it. They are “Indians” no longer. Flinders is also sure to try and move beyond bartering and has simply left gifts for these unseen Australians: hatchets, ropes, cups and the like. Hopefully, goodwill might be purchased with these gifts, the better to benefit “succeeding visitors”[3].

Peter FitzSimons

[1] Matthew Flinders, Voyage To Terra Australis Vol.1, G. and W. Nichol, London, 1814, p. 146

[2] Matthew Flinders, Voyage To Terra Australis Vol.1, G. and W. Nichol, London, 1814, pp. 146-147

[3] Matthew Flinders, Voyage To Terra Australis Vol.1, G. and W. Nichol, London, 1814, pp. 146-147

Charts of Matthew Flinders

Matthew Flinders was born on March 16 1774 in Donington, Lincolnshire, England. With George Bass, he confirmed Tasmania, then named Van Diemen’s land, as an island and in 1802-03, he led the first inshore circumnavigation of Australia. Flinders is also credited as the first to use Australia as the continent’s name. He died in London on July 19, 1814. He was 40 years old.

Peter FitzSimons’ forthcoming book on Flinders will be published by Hachette.

Footage by Craig Bender

More from the Museum

The Australian National Maritime Museum celebrates our nations's history and connection to the sea. We protect the National Maritime collection, a rich and diverse range of over 160,000 historic artefacts.

Among these objects are fascinating treasures, such as a copy of Flinders' A Voyage to Terra Australis and an array of charts based on these important surveys of Australia's coatline.

00004101 - Chart of Van Diemens Land, 1798 - 1799. Matthew Flinders, engraved by L Welsh.

ANMM Collection

Heroes of Colonial Encounters, Helen S Tiernan, 2017

ANMM Collection reproduced courtesy of Helen S Tiernan and licenced for use by the Museum. If you would like to use this image please contact the Museum at images@sea.museum

While Matthew Flinders circumnavigated the Australian continent he was assisted by Bungaree, who acted as a type of diplomat with other First Nations people they encountered on the voyage. As a consequence Bungaree became the first known person born in the country to circumnavigate it.

Although Bungaree became well versed in the ways of the new inhabitants and took to wearing elements of European dress, he remained very much a Kuringgai man and a respected elder amongst his people. The last years of Bungaree's life were spent in Sydney on the land now known as The Domain. He died on Wednesday 24 November 1830 and was buried at Rose Bay.

Read more about Flinders and Bungaree